Another man-made flooding fiasco in the making on Johns Island

The city of Charleston is allowing developments on Johns Island to make many of the same mistakes that led to severe drainage problems in other areas, including outer West Ashley’s Church Creek basin.

Developers are using building methods that disrupt the land’s natural capacity to absorb water, causing a compounding problem as more subdivisions multiply without a coordinated drainage plan in the fastest-growing part of the city. Recently developed areas along River Road, as well as Maybank Highway near the Trophy Lakes community, already are flooding.

City officials say they’re studying how developments shift drainage patterns in the overall watershed, and that could lead to stricter stormwater regulations for the island’s future developments.

“We don’t have that full watershed understanding as we did for Church Creek,” said Kinsey Holton, the city’s stormwater program manager. “We’ve started that on Johns Island.”

But many Johns Island residents are outraged that those problems were created in the first place, especially since the Johns Island Community Plan adopted more than a decade ago was supposed to prepare the island for development.

When the community plan was drafted under then-Mayor Joe Riley, Johns Island was poised to be Charleston’s next frontier for development, and it posed a unique opportunity for the city to establish what should be built, where, and how it would all make sense in a mostly rural environment.

It pinpointed the best spots for high-density projects, including higher ground along Maybank Highway. But it also called for sustainable building practices to limit runoff and protect the island’s sensitive, coastal ecosystem. It said projects should have a “light footprint” on the land, and that low-lying properties near the river should be considered “unsuitable for neighborhood development.”

The large majority of the plan’s recommendations have been loosely followed, if at all, because the city never backed them up with policy changes to enforce them. Swampy forests are now being cleared and filled in with a mix of sand and clay, materials not as absorbent as the land’s natural soil. Some developers are using it to raise their land, sending a cascade of stormwater to lower-lying properties.

Brad Nettles bnettles@postandcourier.com

And while the city can encourage developers to use natural soil and porous pavements to limit runoff, Holton said most projects tend to follow the base-line requirements that were written without an understanding of how the watershed naturally works.

Any new regulations would apply to projects that haven’t been approved to date. Currently, 29 housing developments planned or under construction on the island have a combined footprint of about 2,213 acres, almost half the size of Charleston’s peninsula.

Many Johns Island residents worry that with rising seas and more intense storms, the window of opportunity is closing to prevent planning flaws from becoming major catastrophes.

“If you continue to ignore this, 20 years from now we’re going to be spending millions of dollars to bail out subdivisions that aren’t built yet,” said Mark Brandenburg, who lives in the older Stono Pointe community off of River Road.

‘Sponge forests’ disappearing

Dozens of Johns Island residents have been showing up to city meetings over the past few weeks to urge City Council, Mayor John Tecklenburg and the Planning Commission to take a closer look at the development practices on Johns Island. Nearly 3,000 people — about a third of the island’s population — have signed an online petition to stop destructive building practices such as clear-cutting forests.

Phil Dustan, an ecologist at the College of Charleston who lives in Stono Pointe, is among the most vocal leaders in the fight. He was on the committee that helped draft the Johns Island Community Plan. Recently, he’s taken council members Carol Jackson and Marvin Wagener on a tour of some construction sites along River Road, where crews have been cutting down trees, digging up the roots, and replacing the topsoil with a new layer of sandy dirt.

These trees, he said, are particularly important for drainage.

“I call them sponge forests,” he said. “They’ve evolved to suck up water.”

Brad Nettles bnettles@postandcourier.com

Dustan has studied the area’s topography with geologist Norman Levine, also from the college. Their research shows a dune-like pattern across Johns Island, with ridges and swails running parallel to the coastline. Historically, people settled in the higher lands and farmed in the rich soil found in the lower points.

As farming faded, forests grew back in and helped absorb runoff from the communities on higher ground. Now, developers are building homes in those lower areas, and the city doesn’t currently require them to use the land’s natural assets to absorb water.

The city does have a strict policy to make developers protect grand trees, but Dustan said it’s the overall forest that’s so critical for an area’s drainage. Plus, in many projects, developers have followed the city’s regulations by putting a fence around the protected trees and then filling in dirt around them. The trees end up in a well that fills with water whenever it rains, eventually drowning them.

Brad Nettles bnettles@postandcourier.com

Holton said the city now realizes tree wells are problematic, and they won’t be encouraged anymore in future projects.

Holton’s job is to review developments’ drainage systems. He said 90 percent choose to use detention ponds. To make them work in lower-lying areas, many raise their foundation with the sandy clay to create enough of a slope from the ground to the pond. That’s why many of them clear-cut trees and remove the top soil.

Developers can choose which drainage method to use from the city’s stormwater manual. Less intrusive options include porous pavements and rain gardens. But they’re often overlooked.

“When it comes to drainage, not a lot of people go above and beyond,” he said.

George Reavis, a developer of a 33-unit project on Maybank Highway, said those systems can be costly.

“These types of methods are expensive and can drive up the cost of housing to make it unattainable, at least for the market that we’re trying to satisfy,” he said.

When Richie McCullough decided to move to the area from Lexington with his wife about a year ago, a real estate agent told him Johns Island was “the next Mount Pleasant.” They bought a house in the brand new Stonoview community between River Road and the Stono River. They didn’t realize the developer planned to raise the land behind them two feet to build another row of houses.

“Now, every bit of rain that comes, or even the snow that came, the runoff is rolling into our backyard,” he said.

Residents who live near the new Whitney Lakes neighborhood say they’re having the same problem.

Holton said the city doesn’t regulate how developers use fill material to elevate their land.

“It does allow one property owner to fend water off onto another property owner, and it’s a really complicated issue that a lot of municipalities are dealing with,” he said.

The city recently partnered with the Green Infrastructure Center, a Charlottesville, Va.-based nonprofit, to study the connection between trees and flood mitigation. The organization has recommended that the city stop allowing developers to clear-cut forests, and require them to use the land’s natural soils. Otherwise, the consultants said the island’s developments will continue to cause flooding problems and water quality issues.

Growth in low-lying areas

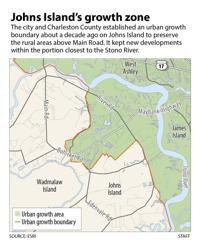

When the community plan was written, the city established an urban growth boundary with Charleston County to preserve the rural areas above Main Road, corralling new developments to the portion closest to the Stono River. But the boundary line wasn’t drawn with topography in mind, so, inadvertently, it encourages growth in some of the lowest-lying areas.

For instance, a 201-acre parcel on the Stono River near Dustan’s property is zoned for residential development. The developer, American Star, has plans to build 205 homes on the site, which in some places sits as low as 5 feet above sea level. Dustan’s maps show how the property would be inundated by storm surge similar to Tropical Storm Irma, which reached 9½ feet.

The Planning Commission deferred a decision on the project last week, but several commissioners reminded the crowd that they can’t reject a proposal if it meets the legal requirements laid out in the city’s approval process.

Brad Nettles bnettles@postandcourier.com

If a property has zoning in place, and practically all of them do, the city can’t turn down its development, regardless of how low or vulnerable the site might be. The city’s only option is to change the zoning, but it’s not a popular process.

“The arbitrary taking of property rights is not something that is easily done, or necessarily even desirable,” said City Planner Jacob Lindsey.

Lindsey and city spokesman Jack O’Toole said the city must be able to justify any zoning changes with hard evidence that can be presented in a courtroom.

Regulations on the state and federal level help protect the environment, but they haven’t been effective in keeping developments from getting built in the city’s high-risk areas. The state office of Ocean & Coastal Resource Management requires developers to get a permit before disturbing land along the coast. The Army Corps of Engineers oversees approval of the filling of any wetlands, but President Donald Trump aims to scale back those regulations to make it easier for developers.

But it’s the city that’s liable for future drainage problems, and it already faces $2 billion worth of drainage and resiliency projects, not to mention the $10 million the city and the Federal Emergency Management Agency are spending to buy out 48 flood-prone homes in the Church Creek drainage basin.

Jason Crowley, the communities and transportation program director with the Coastal Conservation League, said that the city should use its zoning power to limit residential developments in low-lying areas, as the Johns Island Community Plan called for. After all, it already has strict controls on what property owners can do in the peninsula’s Historic District, he said.

“If we have the legal right to restrict property owners based on historic value of property, why can’t we restrict them based on the ecological value of land?” he said.

The city hasn’t ruled that out, Lindsey and O’Toole said. First, they have to conduct an area-wide drainage study, then update the community plan.